684

By Tracy Moses

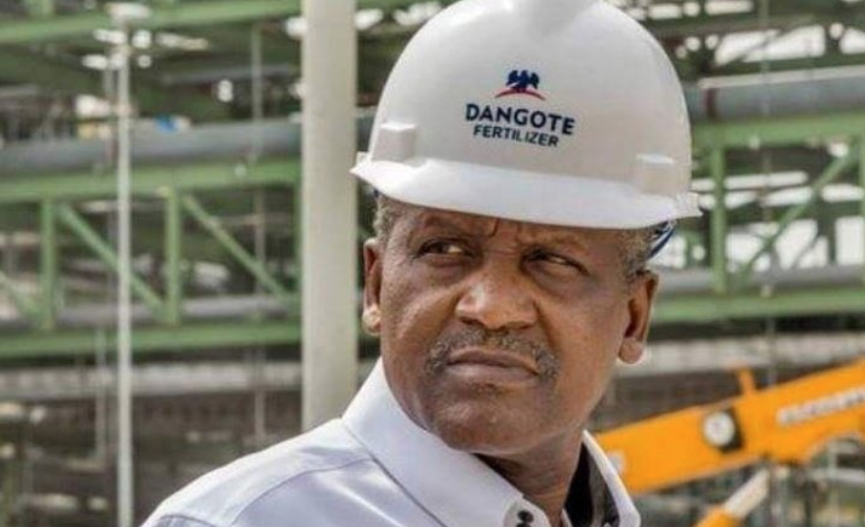

Several private depots across the country, particularly in Lagos on Monday, were left deserted as the Dangote Refinery rolled out large-scale petrol distribution to filling stations in 12 states.

For years, marketers and retailers depended heavily on private depots for supply, but the shift was immediate once Dangote introduced more competitive pricing that operators found impossible to ignore.

At the refinery loading point, petrol was sold at ₦820 per litre, below the prevailing Lagos depot prices. Just last Friday, WOSBAB and AITEO pegged their prices at ₦836, while MENJ charged ₦838. The difference, though seemingly minor, translates into millions of naira in savings for bulk purchases running into thousands of litres, making Dangote the obvious choice for truckers and retailers.

The impact was visible almost instantly. Truck lines disappeared from Lagos depots. At AITEO and NIPCO’s Dockyard depots, activities were at a standstill. The Satellite Town axis also saw no movement at MENJ, First Royal, and Rainoil. In the Coconut area, Sahara, Bono, and Integrated depots recorded zero truck activity.

This trend was not confined to Lagos alone.

Reports from Calabar and Port Harcourt confirmed similar inactivity, underscoring the refinery’s national reach and its ability to rapidly shift the fuel distribution landscape.

Industry stakeholders describe the situation as a classic case of market displacement, with Dangote leveraging its refining power to redefine ex-depot pricing and supply dynamics.

This development comes against the backdrop of Nigeria’s wider energy sector upheaval. In May 2023, the federal government removed the petrol subsidy, a move that immediately tripled pump prices and forced marketers to rely more heavily on private depots for supply. The removal also laid bare Nigeria’s dependence on fuel imports, which historically accounted for over 90% of the country’s consumption despite its status as Africa’s largest crude producer.

Coupled with this was the foreign exchange crisis that gripped the economy throughout 2024 and into 2025. With the naira losing nearly 65% of its value against the dollar within a year, the cost of importing refined products became prohibitive. Depot operators, who had to source forex from parallel markets, were among the hardest hit, often operating at razor-thin margins.

Depot utilization rates reflected the strain. Industry data from the Depot and Petroleum Products Marketers Association of Nigeria (DAPPMAN) showed that by late 2024, average utilization of private storage facilities had fallen to below 40%, as import volumes dwindled and competition tightened.

The entry of the 650,000 barrels-per-day Dangote Refinery into active distribution therefore represents not just a commercial shift but a structural realignment. By offering locally refined products at prices that undercut depot benchmarks, Dangote is exploiting both its economies of scale and the foreign exchange advantage of sourcing crude domestically.

For depot owners, the implications are stark. Many had sunk billions of naira into infrastructure to fill the gap during Nigeria’s decades-long reliance on imports. Now, with their business model eroded, they face an existential crisis. Unless they diversify into allied services, such as logistics, bunkering, or regional exports, or form strategic alliances, many risk being forced out of the market entirely.