938

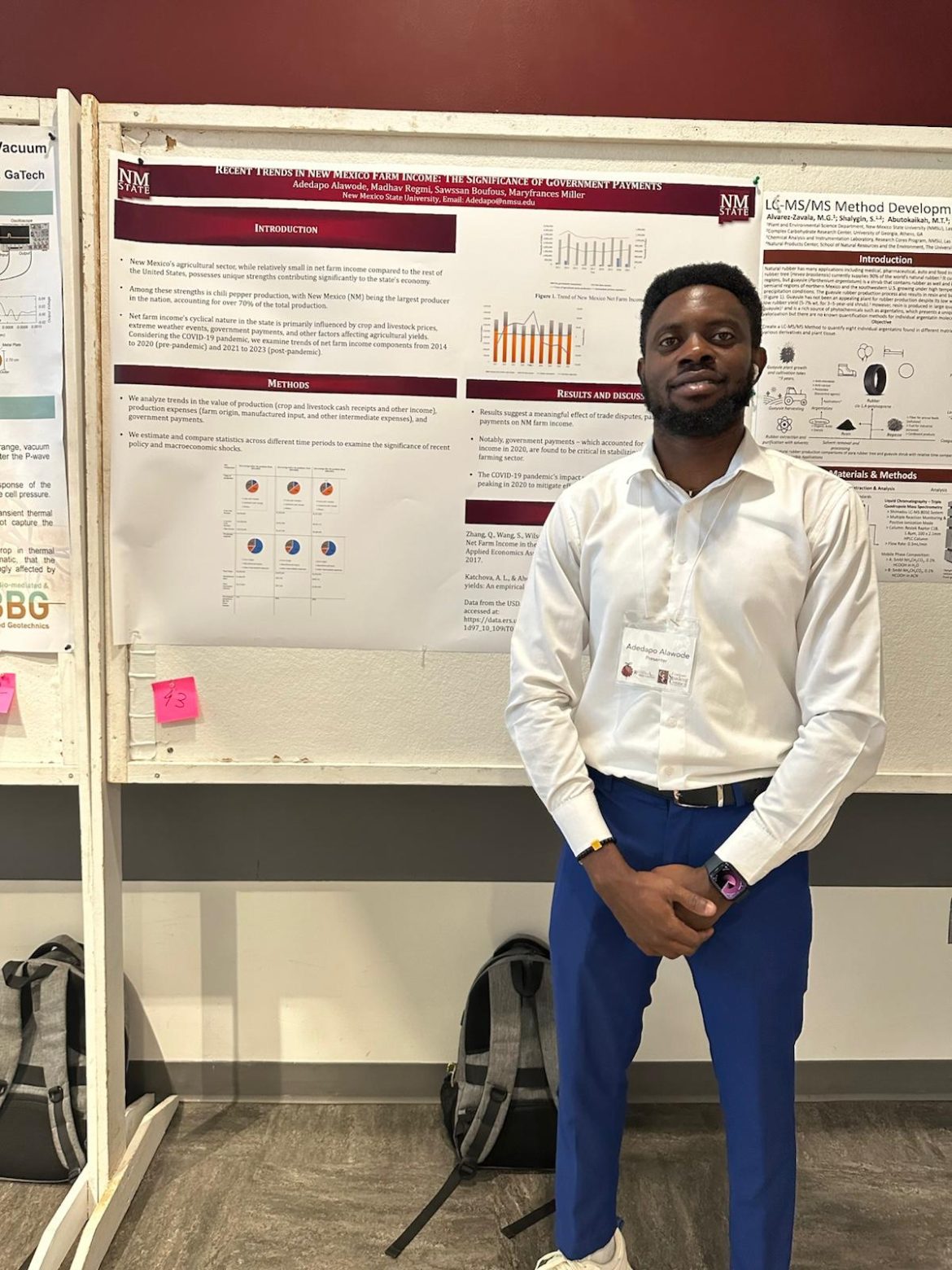

By Adedapo Alawode Emmanuel

The global agricultural economy is hurtling toward an age of unprecedented uncertainty. Climate shocks from droughts to floods, erratic rainfall to extreme temperatures are no longer the exception. They are the norm.

These recurring disruptions make planting and harvesting schedules unpredictable, crop yields and quality less reliable, and food supply chains more vulnerable. The result is wild swings in food prices, at times to levels that crush household buying power, and at other times to a point that destroys farmers’ incomes. The impact of this volatility ripples beyond just producers and consumers.

It reverberates through national budgets, trade flows, and the very goal of global food security. In this time of turbulence, technology can play an important role. Artificial intelligence (AI), long considered a tool for advanced economies and a luxury for the developed world, is increasingly emerging as an essential hedge against volatility.

The power of AI is its ability to sense the coming storm, digitally manage supply chains, and help policymakers cushion the impact on farmers and consumers. The agricultural sector is historically one of the last to adopt digital technologies. But even in the farming industry, more and more experiments are underway to pilot AI as a hedge against climate change.

As an agricultural economist who has spent the last decade looking at the intersection of technology, poverty, and food systems, I am bullish on AI’s capacity to curb volatility, but with one important caveat: if it is deployed equitably, transparently, and with the right kind of policy support.

Climate change undermines agricultural markets along two main vectors. The first is physical disruption. Crop yields and production are curtailed by extreme weather events that can delay or prevent planting, water or fertilize crops unevenly, or damage or destroy entire harvests.

Floods in Pakistan in 2022, for example, inundated more than 2 million hectares of farmland, causing widespread losses in rice and cotton and upending local and export markets. Drought in East Africa has seen successive maize failures in recent years, fueling food insecurity and pushing up regional prices. The second vector is market psychology and speculation.

The fear that climate shocks set off in the marketplace is every bit as disruptive as the physical loss of crops or livestock. Speculative trading on commodity exchanges, panic buying by consumers, and hoarding by traders exacerbate the impact of physical shortages.

The result is volatile swings in food prices that hit low- and middle-income countries the hardest. In the countries where smallholder farmers earn narrow profit margins and where consumers spend the largest share of their income on food staples, even a small increase in the price of maize, rice, or wheat can push millions into food insecurity.

AI can transform our predictive intelligence, supply chain resiliency, and policy responses. Machine learning algorithms that crunch big data from remote sensing, weather forecasting, soil moisture sensors, and past crop yield statistics, for example, have proved adept at pinpointing early signals of crop stress.

Models can forecast pest infestations, water shortages, or potential yield dips months or even weeks before they happen. In India, AI-powered models have been deployed with over 80% accuracy to predict wheat yields and help policymakers adjust procurement levels before a bumper or lean season. In East Africa, early warning systems now use AI tools to parse rainfall anomalies and vegetation indices, helping predict food aid needs before shortages arise. The potential goes beyond forecasting.

AI could also underpin dynamic pricing mechanisms that adjust prices in real time based on future supply and demand signals. If models predict a below-average maize harvest in Nigeria or Kenya, policymakers can calibrate subsidies, reduce import tariffs, or release reserve stocks.

This anticipatory adjustment could preempt some of the wild price spikes and troughs, better protecting both farmers and consumers. In many developed countries, similar AI systems have already been used to stabilize dairy and grain prices, and these experiences can be replicated and tailored to developing world contexts.

AI can also optimize logistics so that food supply chains can be agile and swiftly reroute food from glut regions to deficit ones, ensuring each market has an adequate supply.

The savings on food waste, currently one-third of all food produced globally and tighter, more efficient supply chains can help tamp down volatile price spikes. The perishability of fresh produce, such as fruits and vegetables, creates additional pressures on prices.

AI-enabled cold-chain management, which uses sensors and data analytics to monitor and optimize temperature-controlled storage, transport, and distribution, can ensure these goods last longer and experience less post-harvest loss, further contributing to price stabilization. Governments and aid agencies can use AI simulations to model the impact of different policy measures under a range of climate stress scenarios.

Algorithms could run through a litany of policy responses, such as export bans, upscaling of food aid, fertilizer subsidies, and tax exemptions, to provide near-real time impact assessments. Such AI-driven insights could guide decision-makers to move beyond knee-jerk reactions and take premeditated, strategic action.

AI is not a panacea. The divide between those who have digital access and those who do not is a looming threat.

In Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, many smallholder farmers do not have access to smartphones, the internet, or even the digital literacy to use AI-based platforms. Left to market forces alone, AI will most likely exacerbate existing inequalities between commercial farms that can access AI and family farms that need it the most.

Another digital-access challenge is that many AI models are trained and tested on data from large-scale commercial farms in North America or Europe, which can be quite different from the conditions and systems that characterize smallholder farming in rural parts of Africa, Asia, or Latin America.

Without data that capture the real conditions on the ground, AI predictions may be inaccurate or plain irrelevant for rural farmers. A third set of concerns relate to issues of corporate governance and monopolization. Agricultural data and the AI platforms that crunch them are increasingly concentrated among a handful of big corporations.

Algorithms that power big decisions that affect entire food systems must be open and transparent, and when AI is tied to profit motives and proprietary platforms, those ethical and governance standards can be compromised. Finally, AI implementation is expensive. Low-income countries may be shut out without financing from international aid, public-private partnerships, or open-source AI communities.

AI can make meaningful contributions to agricultural resilience and price stabilization, but only if certain preconditions are met. The first is data. Government, academia, and multilateral organizations must collaborate to invest in local data sources that capture the full diversity of farming systems, environments, and seasons.

The second is inclusion. Farmers, traders, and local communities must have seats at the table to design, test, and implement these tools to ensure AI platforms are usable, trusted, and culturally appropriate.

Third, development organizations must seek out open-source or at least interpretable models that avoid monopolization and guard against lack of transparency.

Fourth, we need to build appropriate governance frameworks to regulate the use of AI and make sure the deployment of AI technologies serve the public rather than private interest alone.

Finally, capacity building will be key to democratizing access to AI. Farmers, extension agents, and policy makers themselves need to be trained and educated in digital literacy to make full use of these technologies.

AI is not a silver bullet, but it is a lever to pull in the fight against climate-driven agricultural price volatility. The tools are here, but they must be applied wisely and within robust policy frameworks, and with the inclusion of all stakeholders. This is not a problem that farmers or governments must solve alone. Private companies and civil society will need to work in tandem as well.

As climate volatility becomes the new normal, the question is no longer whether AI should have a seat at the table of agriculture and food systems. The question is how, wisely and justly, it can be integrated to help protect the security of food and those who produce it – both for smallholder farmers in developing countries and consumers everywhere.

-Adedapo Alawode Emmanuel is a Nigerian U.S based agricultural economist specializing in technology policy, rural development, and sustainable food systems.