957

By Lizzy Chirkpi

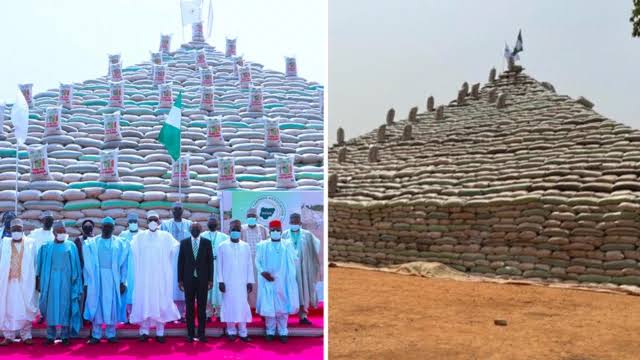

In January 2022, President Muhammadu Buhari unveiled Nigeria’s towering rice pyramids in Abuja, a powerful symbol of the nation’s journey toward food self-sufficiency.

Made of over a million bags of paddy brand, these pyramids were the crowning achievement of the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) Anchor Borrowers’ Programme (ABP), a multi-billion-naira initiative launched in 2015 to boost local rice production in the country.

Today, the pyramids are gone,

dismantled and sold leaving the painful question: Where is the rice?

Nigeria, now Africa’s largest rice consumer, is grappling with a severe crisis. Millions of citizens can not afford a single bag of rice, and the promise of affordable, homegrown produce has collapsed under the weight of inflation, insecurity, corruption, and failed policies.

The rice pyramid once stood tall as a symbol of hope, but symbols do not feed nations. For Nigeria to reclaim food security, it must move beyond spectacle to substance, from lofty dreams to grounded delivery. Until then, for many Nigerians, a plate of rice remains both a meal and a luxury.

The Billions Behind the Dream

The Anchor Borrowers Programme was an ambitious effort to provide small scale farmers with access to low-interest loans, seeds, fertilizers, and equipment. The ultimate goal was to replace rice imports with homegrown produce.

More than ₦1.1 trillion was disbursed to over 4.8 million farmers cultivating 23 different crops, with rice receiving the largest portion of the investment.

States like Kebbi, Ebonyi, Kano, and Benue were identified as strategic pillars of Nigeria’s rice revolution. Partnerships with the Rice Farmers Association of Nigeria (RIFAN) and large-scale millers were designed to ensure a seamless value chain from paddy to plate.

However, nearly a decade later, the reality is grim. Official CBN documents show that over ₦283 billion was disbursed to rice farmers under the ABP, yet more than half of about ₦146 billion remains unpaid. Even worse, much of the rice expected to reach markets never did. While some beneficiaries were expected to repay in produce, thousands defaulted. Others sold the subsidized inputs on the black market, and some recipients were not farmers at all.

According to Dr. Babu Zakari Bello from the Federal University of Dutse’s Department of Environmental Management while speaking to Pointblanknews.com, the failure of the scheme stems from a lack of proper planning and implementation.

“If there’s no planning in the intervention, then it cannot be implemented and it will be haphazardly implemented,” he explained. Dr. Bello further noted that the funds often failed to reach the intended targets.

“In most of these interventions, the distribution is marginalized. I don’t want to discuss politics but this is a common practice in Nigeria; you see interventions targeting people, but when you try to trace the beneficiaries, you find out that it is in the wrong place.”

He recounted an instance where a politician distributed pumping machines to farmers, only for them to be immediately resold. “So the problems are at each level, so we need to have a mindset from top to bottom,” he concluded.

From Pyramids to Empty Pockets

The collapse of the rice pyramid dream is reflected in today’s market realities. In 2015, a 50kg bag of rice cost about ₦12,000 to ₦15,000. Today, in 2025, that same bag goes for between ₦75,000 and ₦105,000, far beyond the reach of most Nigerians. To put this into perspective, the new national minimum wage, still under debate as of August 2025, is ₦62,000 barely enough to buy a single bag of rice.

Food inflation has been a major driver of economic hardship. In July 2025, Nigeria’s food inflation rate stood at 22.74%, outpacing general inflation, which was 21.88%.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), over 31 million Nigerians are facing acute food insecurity this year. Staple meals like jollof rice, once a Sunday favorite, have become unaffordable for lower- and middle-income households.

The much-celebrated Imota Rice Mill in Lagos, commissioned in 2023 and touted as the largest in sub-Saharan Africa, has a processing capacity of 2.8 million bags annually. But its operations have been hampered by insufficient paddy supply.

The mills are ready, but the rice is not available. Rampant insecurity across major rice-producing states like Zamfara and Benue has forced thousands of farmers off their land. Kidnappings, banditry, and farmer-herder conflicts have turned agriculture into a life-threatening endeavor.

Terhemen Yongu, a rice farmer from Gwer West in Benue State, shared his ordeal with Pointblanknews.com: “We can no longer go to our farms because we are afraid of being killed. The herdsmen come with cows to destroy our farms, and whenever we complain, they turn against us. My brother was killed by a Fulani herdsman because he chased his cows out of his farm.”

Even in relatively secure areas, farmers complain about delayed or substandard input delivery. Others allege that political patronage influenced the selection of beneficiaries. In some states, the scheme was reportedly hijacked by “political farmers” and urban elites with no connection to agriculture, who accessed the funds and defaulted without consequence.

Adamu Musa, a rice farmer in Annabi, FCT, lamented: “They gave us inputs late. Fertilizer came when we had already planted. We tried to manage, but the harvest was poor. How do I repay a loan when I can’t even feed my family?”

Ngozi Okoro, a small-scale mill operator in Ebonyi also recounted: “We built a new mill some years ago, expecting more paddy. Now, the machines are idle. There’s no rice coming in. Farmers are tired, and prices keep going up.”

Smuggling, Corruption, and Import Paradox

Adding to the crisis is Nigeria’s continued dependence on rice imports, both official and through pervasive smuggling. Although, the government banned rice imports through land borders in 2019, foreign rice continues to flood markets in cities like Lagos, Abuja, and Port Harcourt. Traders re-bag imported rice and pass it off as local produce. In border towns like Seme and Jibia, rice smuggling remains a booming business, facilitated by corruption at checkpoints.

Mohammed Sani, a rice trader in Abuja, explained: “Most of the rice in my shop is foreign, smuggled through Niger. Local rice is too expensive, and there’s not enough to meet demand. Customers don’t even ask for Nigerian rice anymore.”

For Bassey Bassey, Executive Director of Hipcity Innovation Center and advocacy organization for good governance and accountability said the much-touted rice pyramid was nothing more than a “smoke screen.”

“That rice pyramid was just a smoke screen to make us believe that our farmers were now producing rice that was sufficient enough to feed Nigeria, but in reality, it was not true because it was just for the paparazzi and the likes,” he said.

He believes the intentions behind the ABP were good, but the implementation was flawed. “How can you make such big investments and not monitor?” he asked. “The question is where are those farmers that were given loans and where are the farms?”

Mr. Bassey also dismissed the excuses given by lending agencies like NIRSAL Microfinance Bank, which blamed insecurity and weather for the non-productivity. “We live in a country where people do not lack excuses to justify whatever messy situation they are in,” he stated. “If you are going to invest trillions of naira into a system, I am sure that the consultant must have anticipated some of these risk factors… The idea that insecurity came in, weather issues and the rest does not arise.” He called for accountability, stating that people found culpable should “face the full wrath of the law.”

A System in Disarray

This rice crisis mirrors deeper systemic failings, grand pronouncements without sustainable systems, large spending with minimal accountability, and programs that benefit contractors more than communities.

On July 2, 2024, the House of Representatives began an investigative hearing into the alleged mismanagement of billions in agricultural funding. Hon. Chike Okafor (APC, Imo) stated that over ₦2 trillion had been spent on agricultural interventions in the past eight years, yet food scarcity and malnutrition continue to rise due to the alleged abuse and misapplication of these funds.

Hon. Okafor questioned: “If all this money was truly put into agricultural programs, why is Nigeria in such dire need? Why is there food scarcity? Why do we have an emergency? These are not just figures; they are allegations of abuse, of fictitious farmers, and a broken system.”

While a representative of Sterling Bank claimed it had repaid all its obligations under the ABP, citing a zero naira outstanding balance, these explanations are cold comfort to a nation that remains hungry despite a decade of promises. Nigeria’s rice crisis is a sobering reminder that without transparency, accountability, and a genuine commitment to the people, even the most ambitious projects are destined to crumble.

Upon investigation during the House Committee hearing representative of NIRSAL Microfinance Bank, Charles Bassey, cited insecurity as a major challenge:

“After they had invested the funds in agricultural business, many farmers were not able to return to their farms due to banditry and herdsmen attacks,” he explained.