552

In just ten months, a steady captain has charted new pathways in agriculture, education, healthcare, and security, steering Edo toward a horizon of hope.

By Fred Itua

Ten months is not a lifetime in the history of a people, yet it is long enough for a new rhythm to settle, for the tone of leadership to be felt, and for the stirrings of change to take root. When Governor Monday Okpebholo assumed office, the mood in Edo was one of cautious expectation.

The people yearned for a leader who would not only carry the title but also embody the responsibility, who would not only sit in Osadebey Avenue but would walk in the streets, listen to voices in the markets, and feel the pulse of rural communities.

Ten months on, the whispers across the state are beginning to converge into a common refrain, that something has shifted, that there is a different kind of leadership in play, and that the new man at the saddle has quietly begun to redefine governance in Edo State.

What strikes the observer is not flamboyance or noise but an unpretentious commitment to work. Governor Okpebholo has, in many ways, refused to be carried away by the trappings of office. He has embraced a style that is disarmingly simple yet firmly effective, one that seeks to connect more than it commands, and listens more than it lectures.

This has endeared him to the ordinary people, those who long ago grew weary of grand promises that ended up as footnotes. In these ten months, he has shown that governance can be stripped of excess drama and redirected toward impact.

Roads that had become nightmares of commuters have been rehabilitated; communities previously left in the shadows are beginning to feel the presence of government; and the focus on critical infrastructure, though far from complete, has started to create fresh conversations about possibilities in Edo.

Perhaps the most captivating part of these ten months is not in the projects themselves but in the spirit they have awakened. There is a sense that government is returning to the people, that leadership is no longer about distance and aloofness but about presence and engagement.

Market women talk about a governor who visits without warning; students speak of opportunities opening up; civil servants describe an environment less stifled by bureaucracy and more motivated by accountability. These are not yet the sweeping transformations of a long tenure, but they are the early signs of a different story being written.

It is in agriculture that the governor made his first bold stroke, and the story is best told not in figures but in images. In Etsako, one sees bulldozers ploughing through overgrown land, transforming bush into vast stretches of farmland ready for cultivation.

In Ovia, clusters of women in wrappers and headscarves gather under trees, discussing how to form cooperatives to gain access to the new 3,000 hectares allotted for farming in each senatorial district.

In Esan, a young farmer who once struggled to rent a small piece of land for cassava now looks out over acres cleared by government tractors, his eyes shining with possibilities. This is not politics as usual; this is agriculture as empowerment, a practical attempt to feed the state, reduce dependency, and give dignity back to rural communities.

Education, long a sore spot for Edo families, was another frontier where the governor rolled up his sleeves. Instead of hiding behind reports, he embarked on a school tour that took him from one community to another, peering into classrooms, sitting on broken desks, and speaking directly to teachers and pupils.

In Benin, a headmistress recalls the shock of seeing the governor walk into her school unannounced, observing leaky roofs and crumbling walls. “For the first time, someone came to see, not just to talk,” she said. From that exercise came the resolve to rebuild and rehabilitate schools, starting with the most dilapidated.

The governor also recalibrated the much-publicised EdoBEST programme of his predecessor. While EdoBEST had won applause abroad, many teachers at home complained of its gaps. Okpebholo doubled down, plugging those gaps, ensuring that children had not just tablets and slogans but also safe classrooms, trained instructors, and learning tools.

Today, in parts of Esanland, children who once studied under trees now sit in newly roofed classrooms, their laughter echoing against fresh walls, a reminder that education is more than policy — it is lived reality.

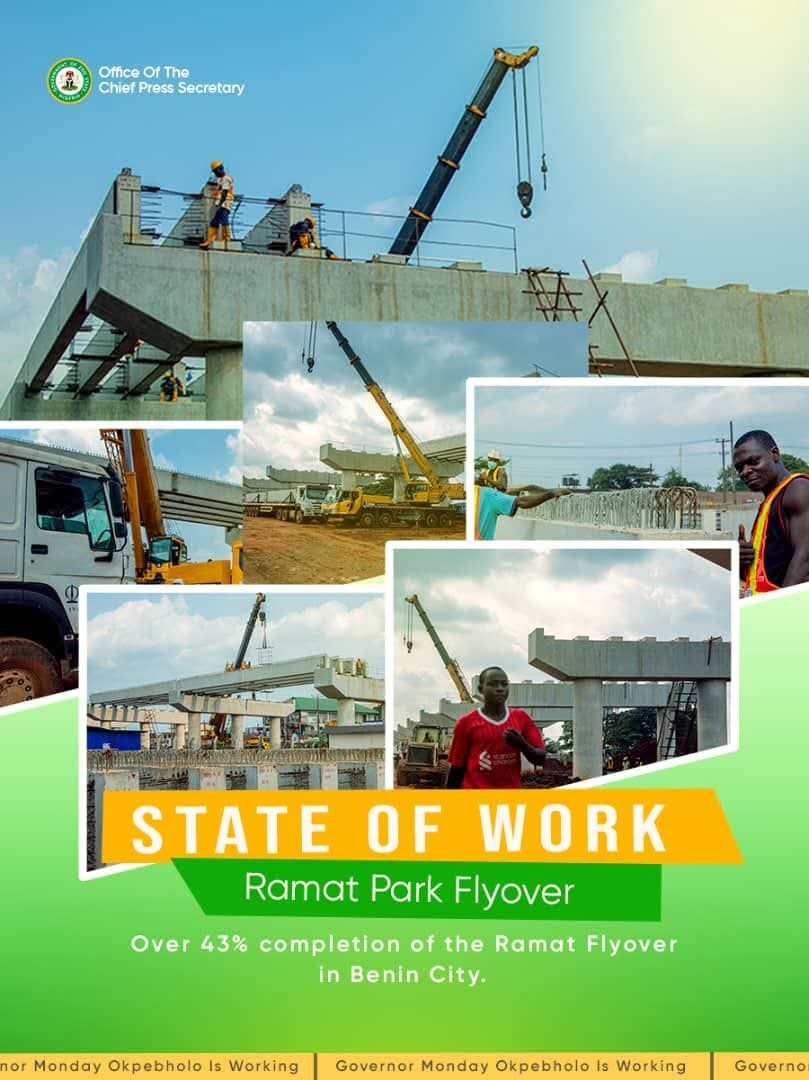

If agriculture is feeding the future and education is shaping it, infrastructure is the backbone that makes both possible. Governor Okpebholo has not shied away from this reality. In Benin City, commuters now speak with relief about stretches of the Benin–Ekpoma road that once swallowed vehicles in gullies but have since been rehabilitated.

In Auchi, traders note how the resurfacing of inner-city roads has revived night markets once abandoned for fear of accidents. Rural communities in Orhionmwon recall the governor’s intervention in long-forgotten feeder roads that now link farmers to markets.

Even federal roads, long neglected and left to the slow grind of Abuja’s bureaucracy, are receiving attention under his watch. Okpebholo has chosen not to fold his arms while his people suffer.

Instead, he has taken responsibility, deploying resources to fix portions of the Benin–Auchi highway and other federal routes, easing the pains of thousands of daily travelers. “These roads are our people’s lifelines,” he remarked in one community meeting, underscoring that to him, governance is not about excuses but about solutions.

Bridges in Oredo and stormwater projects in parts of Benin are no longer just lines in a budget but works in progress visible to the eye. Streetlights flicker to life at dusk along key arteries, a sign that the city is reclaiming its nights from darkness.

These may not yet be the mega projects of glossy billboards, but for the people who walk, trade, and live along these corridors, they are the foundations of renewal.

Healthcare followed a similar trajectory. The governor ordered a full-scale assessment of all primary health care centres in the state, and what was discovered was sobering: buildings without roofs, centres without medicines, clinics where midwives worked with little more than goodwill.

From that moment, a phased renovation began. In a health centre in Uromi, a nurse who once delivered babies in candlelight now smiles as solar panels power her ward. In Akoko-Edo, elderly villagers speak with gratitude of regular outreach visits and stocked dispensaries.

For mothers in Ovia, the difference is striking: a centre once deserted is now open, clean, and equipped. These are not hospitals meant for ribbon-cutting ceremonies; these are centres where life begins safely, where illness is treated with dignity, where healthcare is restored to the people.

But perhaps nowhere has the governor’s resolve been more tested than in the area of security. Edo has known the scourge of cultism and the menace of kidnapping. These two monsters threatened to steal the shine from the state, casting a shadow over its industrious youth and vibrant communities.

Okpebholo chose to fight back, not with mere rhetoric but with decisive measures. Security agencies were strengthened with new patrol vehicles, motorcycles, and logistical support. Vigilante groups were incorporated into a broader security framework.

Laws were invoked and enforced with unusual firmness. In Benin, young men who once terrorised streets under the cover of cult groups are finding their activities curtailed. In Auchi, a vigilante leader speaks proudly of how police response has improved since the arrival of new patrol vehicles.

In Uromi, families recall a chilling wave of kidnappings now checked by coordinated patrols. Slowly but surely, fear is giving way to confidence, and communities are beginning to reclaim their peace.

Beyond bricks, mortar, and asphalt, Okpebholo has also turned his gaze to the invisible foundations of governance — the rules that determine how money is spent. Procurement, once a murky process riddled with suspicion, is being reshaped into a beacon of transparency.

Anchored on the Edo State Public Procurement Law 2020, the governor has strengthened the Edo State Public Procurement Agency, insisting that every kobo spent must reflect value for the people. Officers with vested interests are now compelled to recuse themselves, eliminating collusion and contract inflation.

Contractor registration is automated, an online portal is underway, and contracts are being broken into smaller lots to give small and medium enterprises a fair chance. In this new order, governance is no longer a closed shop for the well-connected; it is an open marketplace where fairness, accountability, and value-for-money guide the process. Okpebholo has made it clear: corruption will find no hiding place under his watch.

But perhaps the boldest strokes of renewal are being drawn within the civil service itself — the engine room of governance. For decades, Edo workers had known a system where promotions stalled, pensions lingered, and dignity was outsourced.

Okpebholo is changing that story. Within nine months, his administration absorbed over 4,000 EdoSTAR teachers into permanent employment, recruited more than 1,300 health workers, and employed agricultural extension officers to strengthen the backbone of rural development. He went further, ending outsourced cleaning contracts and directly employing 1,000 cleaners into the civil service — an act that restored both job security and human dignity.

Salaries now come promptly on or before the 26th of every month, with a 13th-month wage paid in December, and Edo stands tall among only three states in Nigeria paying a ₦75,000 minimum wage. Pensioners, too, now breathe easier, as ₦300 million is released monthly for gratuities, alongside ₦1 billion dedicated to clearing arrears dating back more than a decade.

For the first time in years, civil servants in Edo speak not of frustration but of pride, as the service regains its identity, complete with a Civil Service Anthem, a new dress code, and an institutionalized Civil Service Week. It is, in every sense, a rebirth of the workforce that powers governance.

What binds all these interventions together is the governor’s leadership style — understated, humble, yet quietly firm. He is not the type to drown his people in speeches. Instead, he walks into markets unannounced, listens to traders, asks farmers about their challenges, and speaks to teachers without protocol.

A market woman in Ring Road once described him as “the governor who doesn’t shout.” Civil servants talk of a work environment less stifled by intimidation, more infused with fairness. Teachers say he listens, farmers say he acts, and health workers say he shows up. This accessibility has become the heartbeat of his administration, bridging the distance between government and governed.

Ten months is not a lifetime, and it is too early to etch legacies in stone. Yet, it is long enough to sense direction. And in Edo today, the direction is unmistakable. It is seen in green farms where bush once grew wild. It is felt in classrooms where children no longer sit on bare floors.

It is lived in clinics where mothers no longer travel hours to deliver their babies. It is heard in communities where gunshots of cult gangs no longer drown out the laughter of youth. It is the story of a governor who, without fanfare, is weaving hope back into the fabric of Edo.

Ten months may be too early to etch legacies in stone, but it is long enough to sense direction. And in Governor Monday Okpebholo, Edo has found a leader who, without theatrics, is charting a course of hope. He is proving that leadership need not be deaf, that politics need not be distant, and that the office of governor can once again feel like the office of the people.

In the years to come, Edo will measure his tenure not just by the kilometers of roads built or the schools rehabilitated, but by this renewed confidence that government can indeed be about service, that leadership can once again inspire trust, and that the covenant between ruler and ruled can still be honored.

Ten months have passed, and already, the once-cautious expectations are giving way to something sturdier: belief. Belief that the governor’s simplicity is strength, belief that his listening is leadership, and belief that Edo is on the cusp of a story worth telling for generations.

The journey is still young, and challenges remain. There will be obstacles ahead, and the true test of leadership lies not only in beginnings but in endurance. But as Edo looks back on the first ten months of Governor Monday Okpebholo, the people see not a man overwhelmed by the saddle but one firmly gripping the reins, guiding the state with calm, clarity, and compassion.

The verdict, whispered in markets and spoken in villages, is already clear: this is governance not for the gallery but for the people, not about noise but about substance. Edo has begun a new chapter, and the story, though still unfolding, is already compelling.

-Mr. Fred Itua is the Chief Press Secretary to Governor Monday Okpebholo of Edo State.